The city of Kyoto was the only great city of Japan to be spared serious bombing during World War II, despite being among the top targets preferred for the atomic bomb, thanks to the unprecedented and extraordinary efforts by the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, to protect it. I have written at length on this, and why I have come to think that the issue of Kyoto is actually the key to understanding quite a lot about Truman and the bomb, both prior to and after its use. Whenever the issue of Kyoto comes up in popular discussions, however, one other assertion always arises: that Stimson saved Kyoto because he spent his honeymoon there.

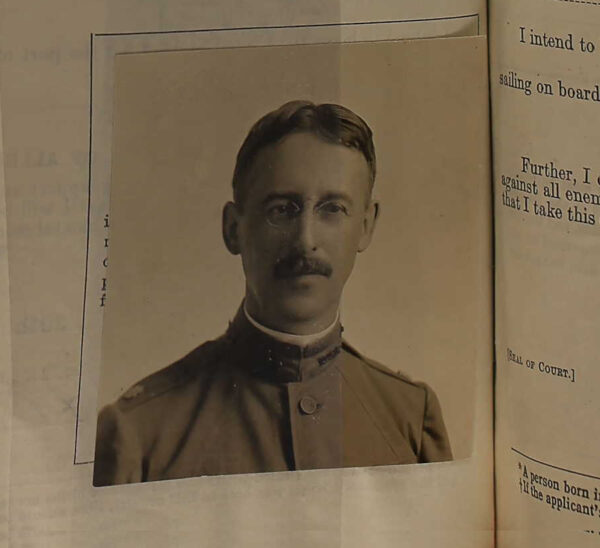

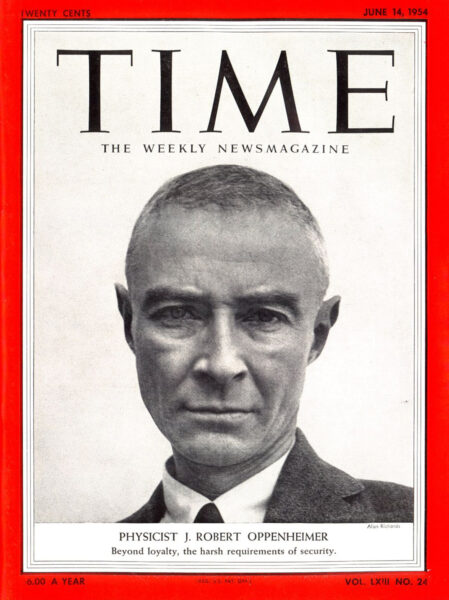

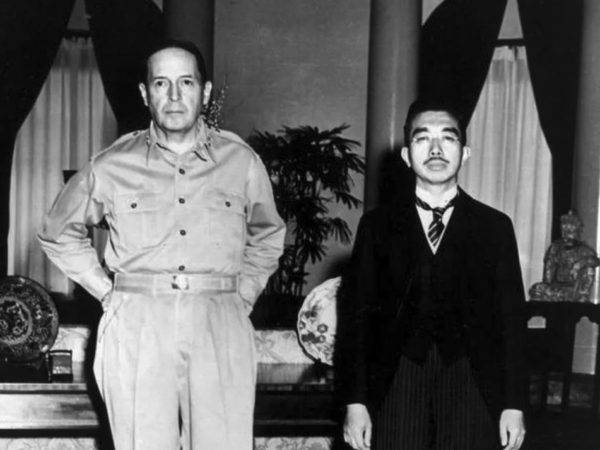

Stimson was not invited by Truman to attend the Potsdam Conference — his rivals, like Byrnes, appear to have gotten him excluded — but the “old man” showed up anyway, with this defiant look on his face. Truman would tell him that he was glad, as Stimson was Truman’s primary conduit of information about the Trinity test and the atomic bomb.

This is used for one of the very few deliberately humorous notes in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023) film, which came out last week. I am in the process of writing a longer review of that, and will probably post something else on it here, but it has served as an instigator for me to push out a blog post I had been working on in draft form for several months about this question of the “honeymoon.” As the post title indicates, my conclusion, after spending some time looking into this, is that the honeymoon story is more probably than not a myth. Stimson did go to Kyoto at least twice in the 1920s, but neither trip could be reasonably characterized as a honeymoon, and explaining his actions on Kyoto in World War II as a result of a “honeymoon” is trivializing and misleading.

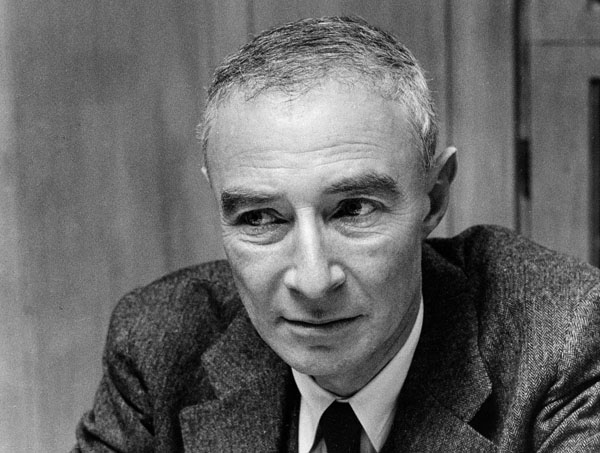

Nolan’s portrayal of Stimson is, well, not very charitable. Within the narrative construction of the film, Stimson exists to emphasize a growing theme of Oppenheimer becoming sidelined as a “mere” technical expert by the military and government officials. In the one meeting that Stimson appears (it is a fictionalized version of the May 31, 1945, meeting of the Interim Committee that Oppenheimer attended as a member of a Scientific Panel of consultants), Oppenheimer strains to get Stimson and others to see the atomic bomb as something worth taking seriously as a weapon and long-term problem. (This was the same meeting in which Oppenheimer reports on the Scientific Panel’s conclusions against a demonstration of the bomb.)

In the film, Stimson expresses some skepticism at the impressiveness of the bomb (Oppenheimer has to convince him otherwise), shoots down any suggestions about warning the Japanese ahead of it, impresses on the men there that the Japanese are intractably committed to war in the face of defeat, and then agrees that the atomic bomb might save American lives. He then, at the end, looks over a list of 12 possible targets, and without fanfare or opposition removes Kyoto from the list, smiling and saying it was an important cultural treasure to the Japanese, and incidentally, where he and his wife had their honeymoon. In both showings of the film, this gets a big laugh. We’ll come back to that laugh.

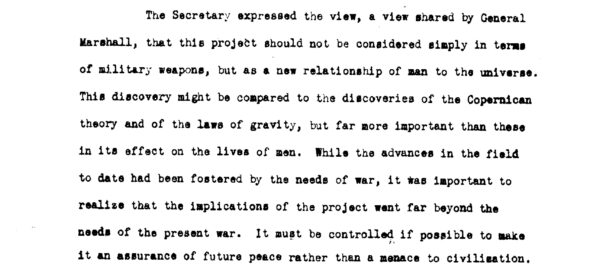

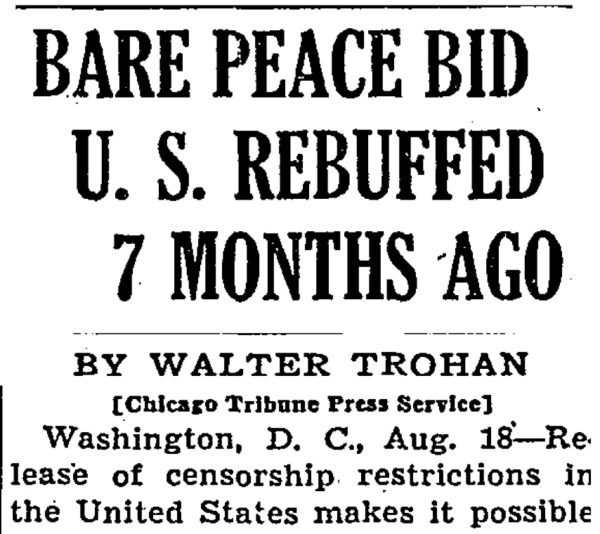

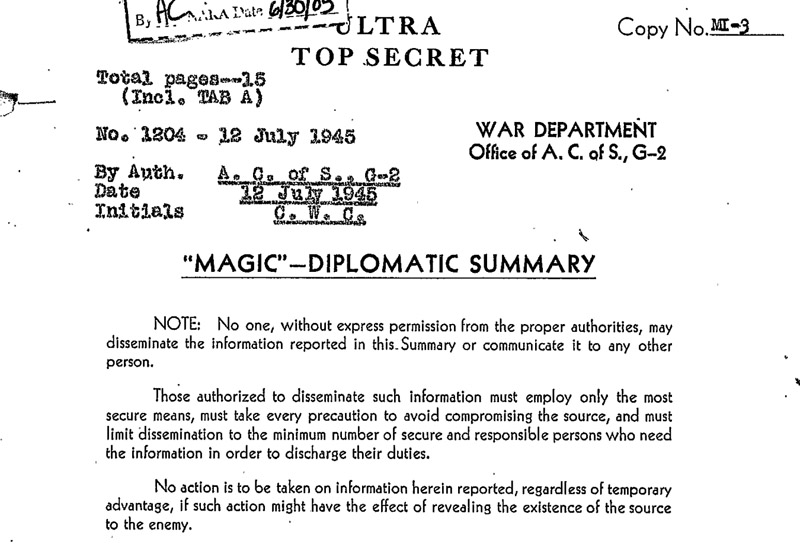

The reality of Stimson, and that meeting, is a lot more complicated than that. One could unpack each of the various components of that meeting as depicted in the film (they are all wrong in some way), but I would just emphasize that Stimson was probably the most high-placed government official to see the atomic bomb in the kinds of terms Oppenheimer cared about. Stimson was the highest-ranked government official to closely follow the atomic bomb’s development, and cared deeply about it as a wartime weapon and as a long-term issue. (His interest in the atomic bomb was essentially the only reason he had not retired from his office.) He absolutely did not believe the Japanese were intractable (he was one of those advocating for a weakening of the terms of unconditional surrender, because he understood the Japanese need to protect their Emperor, even before the MAGIC decrypts showed concrete evidence of this as a sticking point), he absolutely did not frame the atomic bomb’s usage as something that would save American lives. To give a sense of Stimson’s mindset, here is how Stimson opened the May 31, 1945, Interim Committee meeting, according to the minutes:

The Secretary [Stimson] expressed the view, a view shared by General Marshall, that this project should not be considered simply in terms of military weapons, but as a new relationship of ·man to the universe. This discovery might be compared to the discoveries of the Copernican theory and of the laws of gravity, but far more important than these in its effect on the lives of men. While the advances in the field to date had been fostered by the needs of war, it was important to realize that the implications of the project went far beyond the needs of the present war. It must be controlled if possible to make it an assurance of future peace rather than a menace to civilization.

Could one imagine a sentiment more aligned with that of Oppenheimer’s? Anyway, I digress — but my point is to emphasize that the movie does Stimson dirty here, in turning him into a dummy stand-in representing “the powers that be” and how much their interests could diverge from Oppenheimer’s. In reality, Oppenheimer’s positions were pretty well-represented “at the top” for quite some time; making him into an “outsider” here, I think, obscures the reality quite a bit. There will be more on this in my actual review.

But let’s get back to the question of Kyoto and the alleged “honeymoon.” I don’t mention the “honeymoon” story in my own work, because I’ve never been able to substantiate it, despite trying. I am quite interested in the events that led to Kyoto being “spared” from the atomic bombing (and all other bombing) in World War II. I believe, and will be writing quite a bit more on this in my next book, that this incident has not been taken seriously enough by historians. For one thing, it was the only targeting decision that President Truman actually directly participated in, when he backed Stimson in removing it from the list. For another thing, the fact that Truman was involved at all was because Stimson was (correctly) afraid that the military (in the personage of Groves and his subordinates) would not recognize his authority as a civilian to make “operational” decisions of this sort. So it is an important moment in the question of civilian-military relations regarding nuclear weapons. And I believe there is other significance to the Kyoto incident that I have written on elsewhere, and will write on more in the future. The point I’m trying to make is that perhaps more than others, I have really wanted to get into the ins-and-outs of the Kyoto question, including Stimson’s motivations, for some time now.

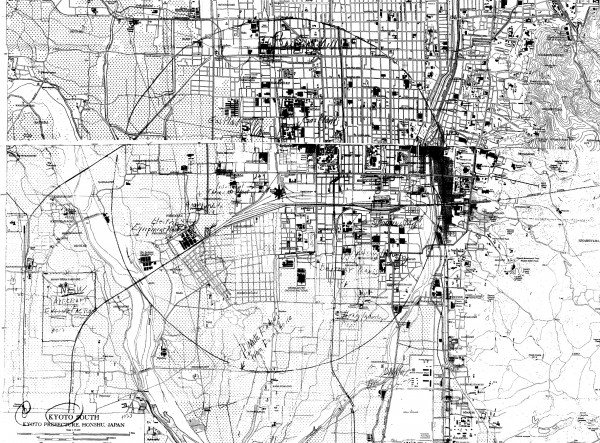

Target map of Kyoto, June 1945, with atomic bomb aiming point indicated, from General Groves’ files — a sign of how far along the plans were for Kyoto to be the first target of the atomic bomb. For more on the non-bombing of Kyoto, see my 2020 article.

I’ve come to the conclusion, after digging and digging, that the “honeymoon” story is false both in its strict sense (in the sense that Stimson did not “honeymoon” there, under any reasonable definition of “honeymoon”) and in its broader sense (attributing his actions on Kyoto during the war simply to that is misleading). I was suspicious of it early on, when I found that no serious sources actually asserted this apparently-verifiable fact, and because it has a “too clever by half” feeling to it. It feels like a “fact” that was a factor tailor-made for catchy headlines and click-bait news stories, the notion that an entire city and the million people who lived there were saved by the fortunate fact of a pleasant trip of a single man. Now, history often does have such coincidences and idiosyncrasies, to be sure. But you’ve got to be on the watch for fake ones, for half-rumors that get elevated to the status of full facts — especially when such “simple” explanations get used at the expense of interrogating more complex ones.

None of the serious, scholarly accounts of the Kyoto incident mention that he took a honeymoon there. Stimson himself never claimed this in any of his published writings, from what I have been able to find. There are, as well, several biographies and even an autobiography of Stimson. Thanks to the essential service of the Internet Archive, perusing these quickly is a trivial task. Here are the ones I looked at, searching for any discussion of a honeymoon to anywhere, coming up with nothing:

- Richard N. Current, Secretary Stimson: A Study in Statecraft (Rutgers University Press, 1954)

- Robert Ferrell, Frank B. Kellogg, Henry L. Stimson (Cooper Square Publishers, 1963)

- Godfrey Hodgson, The Colonel: The Life and Wars of Henry Stimson, 1867-1950 (Knopf, 1990)

- Sean Malloy, Atomic Tragedy: Henry L. Stimson and the Decision to Use the Bomb Against Japan (Cornell University Press, 2008)

- Elting Morison, Turmoil and Tradition: A Study of the Life and Times of Henry L. Stimson (History Book Club, 2003 [1960])

- David F. Schmitz, Henry L. Stimson: The First Wise Man (Scholarly Resources, 2001)

- Henry Stimson and McGeorge Bundy, On Active Service in Peace and War (Harper and Brothers, 1948)

Now, not all of the above are as equal in rigor or quality as the others. (Of them, Morison, Hodgson, and Malloy are the ones which dive deepest into his early life.) And yet not one of the above authors has any indication towards the “honeymoon” story. Would not a single of the above authors found it an interesting thing to point out, had they come across any positive proof of it? And it is not that the above do not discuss the Kyoto incident — many of them do, although they do not take it as centrally important as I do. It is often discussed in terms of the apparent contradiction of Stimson’s “old values” (not bombing cities) with his advocacy of the atomic bomb use in general. If the Kyoto “honeymoon” story was true, surely that would inform such a discussion. In addition to the above, I also looked at scholarly articles in JSTOR, and it shows up in the work of no scholars of World War II history, either.

Did Stimson have a honeymoon? Yes. But to where? That is somewhat unclear, but it doesn’t sound like Asia. Henry Lewis Stimson married Mabel Wellington White in New Haven, Connecticut, on July 6, 1893, after a long and difficult five-and-a-half-year courtship. The delayed marriage was in part to Stimson wanting to secure a solid career “position,” which by 1893 he had done: he had been, at the age of 25, made full partner in the law firm of the famous and prestigious Elihu Root, and his star would just continue to rise from them onward. Their wedding was of sufficiently high social class to carry a notice in both the New York Times and the New York Sun. The only indication that they took any kind of honeymoon that I have found comes from the Times‘ announcement, which mentions that: “The wedding tour of Mr. and Mrs. Stimson will last several weeks.”

It is hard to get a firm sense of where Stimson may have gone in this period. This is several years before he began keeping a daily diary (he started in 1909, and it was originally not very verbose in any event). Morison says that “from 1893 through 1903 he went either to Canada or, more frequently, to the old stamping ground in the West.” He mentions trips to Europe, including a climbing of the Matterhorn in 1896, and hiking in Montana. He mentions no trips to Asia in this period, and no honeymoon. Again, one would think, especially given his later high involvement with the affairs of several Asian nations, that if there was such a trip, it would have been noticed and noted. Again, none of the above biographies of Stimson imply that he honeymooned in Asia, nor his autobiography.

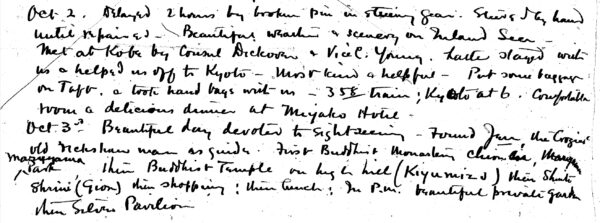

The end of Stimson’s 1926 “Trip to Orient” diary, in which he mentions his arrival to Kyoto: “Kyoto at 6. [???] room a delicious dinner at Miyako Hotel. October 3rd. Beautiful day devoted to sightseeing.”

This was not really a pleasure trip. Stimson treated it largely as a “fact-finding” mission regarding complicated diplomatic relations with regards to Asian nations and the United States, and had been invited by the Governor General of the Philippines, General Leonard Wood, a friend of Stimson’s. He documented this trip extensively, in over 80 pages of hand-written notes, mostly about conversations he had with people in the Philippines (including the rather dubious views about the “self-governing” potential of different races of man offered up by the Governor General — a reminder of the colonial and imperial nature of this endeavor). On the basis of his mission, in that impressively inexpert way of elite politics in the 1920s (apparently being rich and smart and connected with other rich and smart people was enough to make one a regional expert) was sufficient to later get him audiences with the President, would lead to Stimson becoming Governor General of the Philippines in two years, and Secretary of State after that. So it was quite an important trip for him.

In mid-September the Stimsons began the return trip, which was more leisurely and included stops in Hong Kong, Shanghai, Peking, Kobe, and Kyoto. In China and Japan, he visited temples, dined with Americans and locals. He describes many things he saw, in all of these cities, as “beautiful.” He arrived in Kyoto on October 6, and wrote that he had a “delicious dinner at Miyako Hotel.” The next day, October 3, he describes a “beautiful day devoted to sightseeing,” mentions a Buddhist monastery and temple “on high hill” (“Kiyumizu“), mentions going into Gion, and other things that are still fun to do there. Then the diary ends, which is both frustrating and remarkable, given that his time in Kyoto is what we care about, and that he documented pretty much every aspect of the trip in detail except Kyoto. Through other evidence, we know that on October 5, the Stimsons boarded a ship at Yokohama which arrived in San Francisco on October 20, so he could not have spent too much more time in Kyoto.

The brief mention of Kyoto in Stimson’s 1929 diary, and his stay (for a second time) at the Miyako Hotel.

Three years later, in March 1929, the Stimsons spent the night in Kyoto. This visit came when Stimson was returning to the United States having ended his position as Governor General of the Philippines, in order to be sworn in as Herbert Hoover’s Secretary of State. It was basically an overnight stay: according to his diary, they arrived around 6pm, went to their hotel, and were on a train to Tokyo by 8:15am.

I would not call any of the above a “honeymoon” under even a broad definition of the term. Certainly Stimson did not appear to call it this in anything he ever said or wrote, which is really what matters. It is also not at all clear, from the above, that Kyoto was particularly “special” to Stimson in any particular way. His 1926 diary entry seems to reflect he had a nice time there. But it doesn’t contain anything that “cracks the code.” (“Sure would hate to see this city ever bombed!”)

I am absolutely fine with suggesting that Stimson had a really nice time in Kyoto, and that he saw it as something wonderful, and that these resonances played a part in his later decision. It is a remarkable city — I visited it myself for several days in 2016, and one can see why it is regarded as an important cultural monument today, with its ancient temples, castles, streets, districts, and so on. (Some of this specialness is a little circular: Kyoto is one of the only major cities in Japan that has significant pre-war architecture and infrastructure because Stimson had it spared.)

But let us posit that Stimson had a special attachment to it because of his trip(s) there. That is not, I don’t think, a totally satisfactory answer to why he went to such lengths to keep it off of the target list — nor, I would say, were his professed reasons, which related to avoiding the postwar animosity of the Japanese — but let us, for the sake of argument, accept that it played a role. This is still something different than saying that his took a “honeymoon” there. It is a rather significant trip (in 1926, anyway) that involved a lot more than sightseeing, and his acquaintance with Asia was not superficial. It was not some kind of kooky coincidence, and in any event, the reasons behind Stimson’s actions on Kyoto were more significant than just having a nice time with his wife.

So where did the “honeymoon” story come from? I haven’t definitively traced the source, but it seems to come purely out of the world of journalism. If you search for “Stimson + Kyoto + honeymoon” in the ProQuest Historical Newspapers Archive (which is not comprehensive, but has many major newspapers in it), the first relevant entry is a bit of British journalism from 2002 (which describes it as his “second honeymoon,” an interesting qualifier). It appears in another British newspaper in 2006, and then “jumps the pond” to the Wall Street Journal in 2008. None of these stories attribute the statement to any source, or any expert, in particular.

Forgive me for implying that these are not what I would consider particularly strong cases of journalistic research. I have not found any invocations of this trope in any databases I have access to (which are considerable). All of which makes me suspect this is a very recent (~20 years old) myth, one propagated by journalists and the Internet into the realm of “fact.” If I had to guess, calling his 1926 trip a “second honeymoon” was a bit of inventive flourish used by a journalist that, because of its potency as an idea, became repeated and repeated until it took status as fact.

So why does this matter? Let’s get back to the Nolan film and that audience laugh I mentioned. Why laugh? Why is it funny, or interesting, to assert that Stimson scratched Kyoto off the list because he honeymooned there? Because it is discordant: one is talking about something of great historical importance and tremendous weightiness (the atomic bombings of Japan) being influenced by the idiosyncratic coincidence of an old man having fond memories of a city. It is deeply unexpected, because it pushes against the idea of the targeting of the Japanese cities as being part of a strictly rational, strategic process.

And so here’s the rub, for me: the removal of Kyoto was due to the idiosyncratic sensibilities of a single person (however inscrutable), and the targeting process was less strictly rational and strategic as most people think. But it was not quite as arbitrary and capricious as “Kyoto was spared because of a honeymoon” would imply, and the trivializing of the sparing of Kyoto obscures the actually weighty issues regarding authority (who decides the targets of an atomic bomb?) and Truman’s actual role in the bombings (far less than people think). There’s an interesting and important story here, and treating it for a laugh is, well, annoying to me, to say the least. But more to the point, we should stop repeating the honeymoon myth. If I were giving an alternative framing for journalists (and others) to use, it would be this: “For reasons both personal and strategic, Stimson fought to remove Kyoto from the target list, and to keep it off the list after the military repeatedly tried to put it back on.” That gives Stimson a bit more credit, for one thing, and also invites further interest, rather than closing the door with a too-clever-by-half explanation.